How does Human Memory Work?

Yesterday's post got me wondering how to better use the ability of memory.

I got this information from a USA today article on human memory. The full article is here

Long-term memory involves three processes: encoding, storage and retrieval.

• First we break new concepts into their composite parts to establish meaning. Furthermore, we include the context around us as we learn a new concept, or experience another episode in our life. For example, I might encode the phrase "delicious apple" with key descriptive ideas — red color, sweet taste, round shape, the crisp sound of a bite — and then such contextual items as '"I'm feeling good because it's a happy fall day and I'm picking apples."

• Second, as we store the memory, we attach it to other related memories, like "similar to Granny Smith apples but sweeter," and thus, consolidate the new concept with older memories.

• Third, we retrieve the concept, by following some of the pointers that trace the various meaning codes and decoding the stored information to regain meaning. If I can't remember just what "delicious apple" means, I might activate any of the pointer-hints, such as "red" or "picking apples." Pointers connect with other pointers so one hint may allow me to recover the whole meaning.

How do our brains consolidate a new short-term memory like "delicious apple" and place it into long-term memory?

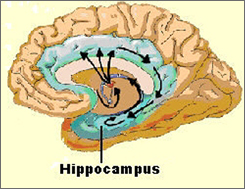

We use the hippocampus, an ancient part of the cortex, to consolidate new memories. An event creates temporary links among cortex neurons. For example, "red" gets stored in the visual area of the cortex, and the sound of a bitten apple gets stored in the auditory area. When I remember the new fact, "delicious apple," the new memory data converges on the hippocampus, which sends them along a path several times to strengthen the links.

The information follows a path (called the Papez circuit), starting at the hippocampus, circulating through more of the limbic system (to pick up any emotional associations like "happy fall day," and spatial associations like "apple orchard"), then on to various parts of the cortex, and back to the hippocampus. Making the information flow around the circuit many times strengthens the links enough that they "stabilize," and no longer need the hippocampus to bring the data together, says neuroscientist Bruno Dubuc of the Canadian Institutes of Neuroscience, Mental Health, and Addiction. The strengthened memory paths, enhanced with environment connections, become a part of long-term memory.

You can play with the concepts above by doing some 'memory experiments'. Pick a simple topic, like 'trains'

Let your memory jump around used that cue as the key descriptive concept. When I did this, I got train memories from all over the world (I have traveled a lot), and from my entire life - from 35 year ago when there was a train track behind my parents hour, to just a few years year ago. One of the things I noticed is that when you remember like this, the older memories have pretty much the same clarity level as the knew ones.

Then I tried adding another level of descriptive association to the memory. 'Red Trains'. This time the subgroup was smaller, and focused on my time living in Germany, where most trains are in fact, painted red.

You can stretch this concept even further. 'Worst Train Ride', got me instantly to a disastrous train journey in Tokyo where I fell asleep, missed my stop, and ended up at the last stop on the line in the middle of the night.

What this process teaches us is that if you can practice remembering things through careful use of keywords or descriptors, perhaps we can both sharpen our memories (by reinforcing them) and increase our ability to utilize memory as a deliberate tool.

Turns out the memory does work a bit like a filing cabinet. The important thing seems to be able to feed in the right key words, and let the memory deliver a string of results. It's a bit like internet search - feed in key words, skim the results, see if you can find the memory that serves our purpose.

As discussed in yesterday's post, what I'm investigating is whether simply using your memory like this in a very non-directed way, is an effective way to put the mind in a creative, empowered state for other more processor intensive tasks like very precise deliberate future visualization. So, far, I've concluding that this is indeed the case - five minutes free associating about trains put me in a great mood, and let me rattle of this post in just a few minutes.

Happy Remembering

I got this information from a USA today article on human memory. The full article is here

Long-term memory involves three processes: encoding, storage and retrieval.

• First we break new concepts into their composite parts to establish meaning. Furthermore, we include the context around us as we learn a new concept, or experience another episode in our life. For example, I might encode the phrase "delicious apple" with key descriptive ideas — red color, sweet taste, round shape, the crisp sound of a bite — and then such contextual items as '"I'm feeling good because it's a happy fall day and I'm picking apples."

• Second, as we store the memory, we attach it to other related memories, like "similar to Granny Smith apples but sweeter," and thus, consolidate the new concept with older memories.

• Third, we retrieve the concept, by following some of the pointers that trace the various meaning codes and decoding the stored information to regain meaning. If I can't remember just what "delicious apple" means, I might activate any of the pointer-hints, such as "red" or "picking apples." Pointers connect with other pointers so one hint may allow me to recover the whole meaning.

How do our brains consolidate a new short-term memory like "delicious apple" and place it into long-term memory?

We use the hippocampus, an ancient part of the cortex, to consolidate new memories. An event creates temporary links among cortex neurons. For example, "red" gets stored in the visual area of the cortex, and the sound of a bitten apple gets stored in the auditory area. When I remember the new fact, "delicious apple," the new memory data converges on the hippocampus, which sends them along a path several times to strengthen the links.

The information follows a path (called the Papez circuit), starting at the hippocampus, circulating through more of the limbic system (to pick up any emotional associations like "happy fall day," and spatial associations like "apple orchard"), then on to various parts of the cortex, and back to the hippocampus. Making the information flow around the circuit many times strengthens the links enough that they "stabilize," and no longer need the hippocampus to bring the data together, says neuroscientist Bruno Dubuc of the Canadian Institutes of Neuroscience, Mental Health, and Addiction. The strengthened memory paths, enhanced with environment connections, become a part of long-term memory.

You can play with the concepts above by doing some 'memory experiments'. Pick a simple topic, like 'trains'

Let your memory jump around used that cue as the key descriptive concept. When I did this, I got train memories from all over the world (I have traveled a lot), and from my entire life - from 35 year ago when there was a train track behind my parents hour, to just a few years year ago. One of the things I noticed is that when you remember like this, the older memories have pretty much the same clarity level as the knew ones.

Then I tried adding another level of descriptive association to the memory. 'Red Trains'. This time the subgroup was smaller, and focused on my time living in Germany, where most trains are in fact, painted red.

You can stretch this concept even further. 'Worst Train Ride', got me instantly to a disastrous train journey in Tokyo where I fell asleep, missed my stop, and ended up at the last stop on the line in the middle of the night.

What this process teaches us is that if you can practice remembering things through careful use of keywords or descriptors, perhaps we can both sharpen our memories (by reinforcing them) and increase our ability to utilize memory as a deliberate tool.

Turns out the memory does work a bit like a filing cabinet. The important thing seems to be able to feed in the right key words, and let the memory deliver a string of results. It's a bit like internet search - feed in key words, skim the results, see if you can find the memory that serves our purpose.

As discussed in yesterday's post, what I'm investigating is whether simply using your memory like this in a very non-directed way, is an effective way to put the mind in a creative, empowered state for other more processor intensive tasks like very precise deliberate future visualization. So, far, I've concluding that this is indeed the case - five minutes free associating about trains put me in a great mood, and let me rattle of this post in just a few minutes.

Happy Remembering